If I ever decide to jack it all in and pursue something vaguely creative, I’m going to become a photo journalist. And I’m going to spend all of my time at railway stations and airports, trying to create portraits of travellers at the end of long journeys, meeting people they’ve not seen for a long time, who they’ve missed deep in their stomachs for an age. There will be pictures of lovers meeting and embracing, of of mothers seeing their children and meeting their grandchildren, and maybe even pictures of people recognising their names written on those little whiteboards that drivers hold up at the airport.

And so it was as we dragged our way into Osaka airport – we’d been travelling for 36 hours with no sleep, but there, just behind the barrier, next to the official drivers holding up their whiteboards, holding up his own paper sign with ‘Mum & Dad’ on it, smiling the thousand watt smile that he’s had since his hair was cut with the aid of a bowl, was ⌗3. There are certain moments when you want time to stand still, where you want to bottle the sheer joy that you’re feeling right at that time , and this was one of them.

⌗3 had travelled out here in March, deciding that the world of medical magazine sales was not for him, and getting approved to teach English in a Japanese school near Kyoto. He went out with, by his own admission, the Japanese vocabulary of a two year old, and went to live in an area where he’d only be able to get by if he spoke Japanese. Mrs E and her friend have a saying that goes along the lines of ‘you’re only ever as happy as your unhappiest child’, and we were keen to know where he was, happiest wise, in a way that we weren’t ever going to get from video calls. And the answer seemed to be very happy indeed – he’d made a lot of progress speaking, writing and reading Japanese, his entertaining approach to teaching English seemed to have resulted in some fabulous feedback from his children and adult pupils, he’d made some Japanese friends, hiked different parts of the country on his days off, gone running most days in Kyoto, and generally seemed to be having a whale of a time.

And because of all of the above, he turned out to be the perfect guide – he had a couple of extra days off just after we’d got there, so in a delightful role reversal, he held our hands through the challenges of getting to our hotel, of finding places to eat, of talking to people on our behalf, of finding interesting places to go; so much so that by the time he.went back to work and we headed to Tokyo on our own, we realised just how lazy we’d been, having to navigate our way about in a city of 37 million people. But more of that later.

We spent the first couple of days in Kyoto, we’d transferred from Osaka on the Huruka ‘Hello Kitty’ themed train, which was, of course, spotlessly clean, on time, and, as it was the end of the line, a guard went into every carriage, pressed a button and the seats all rotated 180 degrees to face forward. Incidentally, guards on trains, after walking through a carriage, will turn and bow to the carriage and its occupants. Something you hardly ever see on Greater Anglia.

A slightly bizarre night eating Japanese pizza, drinking beer and holding hands with the boy; obligatory conversation about Arsenal (& Tomiyasu’s defensive qualities) with the Japanese drinkers at the table next door; then to a hotel for a jet-lagged sleep/non-sleep, before heading out into Kyoto the next morning. Wandered around Kyoto’s temples and shrines and back on the Philosophers’ path, which takes a route around the outskirts of Gion, the historical and slightly touristy district. Gion is also known as the Geisha area, and there are quite a few Geishas walking about – they take very short steps and never seem to travel particularly quickly – we weren’t really sure if that was a style thing or a function of wearing tight kimonos or ridiculous shoes. Gion does a roaring trade in kimono rentals – visitors seem quite keen on the idea of dressing up to wander about between temples, often as couples – as a result, it can feel as if you’re walking about between a series of traditional style newlyweds. Temple wandering was taking its toll just before Mrs E spied a French cider shop just off the Philosopher’s path (what were the chances?) so we got well and truly stung for a couple of miniature glasses of Normandy cider. ⌗3 took us to a specialist vegetarian restaurant that night after he’d finished work – a lovely experience, although the boiled tofu course, served with an enthusiasm and in depth introduction to the restaurant’s approach to tofu manufacture, including the white, green and brown varieties served in a temperature controlled soup dish, really failed to deliver. Effectively, it was like eating three different colours of cardboard – it may have been that our western palates were just not sophisticated to appreciate the nuances involved in tofu appreciation, but it could also be that boiled tofu is about the blandest, most uninspired food on the planet. Still, at least we ate it at optimum temperature. Back to Shimogyo, and to the Izakaya (bar) next to ⌗3’s flat, where he was welcomed like a homecoming king by the bar owner, the cook, and most of the regulars. He showed us a notebook of all the Japanese that he’d learnt from his trips to the Izakaya – what a way to learn! One of the phrases, which he was met with when he went in, was ‘Otsukaresama Desu’, which, roughly translated means ‘Thank you for your hard work’ – it’s used to appreciate anyone who has been at work, earning a crust, keeping the economy going, and for teachers, it’s a very different way of appreciation than what we might be used to at home. ⌗3, like all teachers, is referred to as a Sensei, which translates as ‘Master’, it’s the same for any respected profession. Another expression, by the way, when you want to state an amazing piece of good luck, or to say that a sucker is heading your way, is ‘kamo ga negi wo shottekuru’ which literally translates as ‘here comes a duck carrying a leek on its back’, ie just begging to be cooked.

Morning run to Nijo-jo castle with ⌗3, blistering heat (32 ° at 0800), followed by a walk up to it after a breakfast of Onigiri (rice balls) and coffee from Lawson. There are branches of Lawson absolutely everywhere – you never seem to be more than a block away from one, and if you can’t see one, then there are Family Mart and 7-11 stores which sell the same sort of stuff. They’re known as Konbinis – they’re open all the time and have reasonably decent food and drink which you’re encouraged to eat on the little tables inside the store. It’s frowned upon to eat on the street and definitely on public transport, although on every street, in every station and on the top of mountain summits, you’ll always find a vending machine. Normally drinks, including the weirdly named ‘Pocari Sweat’ sports drink, but also all forms of food, including pizza, souvenirs and toys. ⌗3 gave me a jar of marmalade that he’d bought from a vending machine in the middle of nowhere while on a hike. Despite all of this, there’s no litter anywhere. And no bins – if you have rubbish, you take it home. We walked and ran about in Kyoto for days and didn’t see any litter at all, and it was the same in Hiroshima and Tokyo.

Nijo-jo was worth a visit – it was the original Emperor’s palace, an elaborate structure with Japanese and Chinese painted walls in every room, and a system of status-based waiting rooms, all completely empty of furniture, as all meetings and receptions were held kneeling on the floor. The floors on the walkway around the rooms are made with an elaborate system of supporting joists, and the nails that were used move around when you step on the floorboards, so the building sings – it’s known as a ‘nightingale floor’. It was thought that the squeaky floors were there to alert residents of intruders, although the current thinking is that it’s a design fault. But we’re in Japan, where the idea of a design fault seems very unlikely.

Walked up to the Kiyomizu-dera temple, which was rammed with tourists, but worth it for the views back down over Kyoto and the stunning architecture – most of the buildings were constructed in 1633 and were made without using a single nail. And they’re still up, despite weather and earthquakes, and presumably don’t squeak. To the Izakaya with ⌗3’s friend W for food and more Orion beer in the evening. W is same age as ⌗3 and has already had a past life as an Indonesian Christian missionary before his current role as an engineer. And he’s a big fan of the truly awful ‘Mind Your Language’. So there was quite a bit to unpack there.

⌗3 had a couple of days off, so we spent the first of them hiking from Takao to Hozukyo – taking a bus there and a train from a stunning, if precarious looking, bridge back. The hike started near the Jinjuji temple, where we bought tiny karawake discs to throw into the valley below to cast away bad spirits, then hiked underneath (watching out for flying bad-spirited pottery) to see many more shrines, then to an amazing waterfall reached by hiking up through a small village that had been completely abandoned following a landslide. Fairly creepy, but ⌗3 had told us that he’d done this hike before, and got to the the waterfall where there seemed to be a strange cult ceremony, where an old man appeared to be anointing a series of nubile girls who’d been camping there – they all stopped and stared silently at him when he came into view. He’d done that hike on his own, so I think he was quite grateful of both our company and the cult-free status of the waterfall when we got there.

Back to Kyoto where we spent a reasonable chunk of ⌗3’s inheritance on tickets for the Shinkansen trains for later in the trip, then on to a fabulous restaurant in Karasuma, where we met ⌗3’s friend N, who was good enough to take over the fairly complex ordering process. Amazing food, including a forever soy stock that had been added to each day since the restaurant opened, and some fairly extreme sashimi. N brought us gifts, which made us both grateful and awkward, and mentioned that she had trained Olympic show jumpers and loved animals and liked running – almost as if she’d researched ⌗3’s parents for approval.

Took the Shinkansen to Hiroshima – the Shinkansen was something we really wanted to do – we’d both grown up hearing about the bullet train, so it shouldn’t have been a surprise to see the signs saying it was celebrating its 60th anniversary, but it was, as it just feels so new. And clean. And fast. The seats are like being on a really good aeroplane, similarly the carriages are sealed to avoid passengers hearing the sonic boom that the train makes going into a tunnel. The trains are controlled automatically and were built to avoid roads, so they just ping along at 200 mph on their wide gauge rails which also allow the train to lean without the carriages tilting. Even the bows of the train crew are a different class. And while we’re train-spotting, a quick shout out to the Hankyu line, running between Osaka and Kyoto – worth going on, partly because it’s delightfully retro in style, but also if you wait on the platform to wave to the conductor as the train leaves, he or she will lean out of the back of the train and wave back; not a stately wave, but a proper Japanese one; the conductors all wear white gloves and wave really quickly with their fingers parted, like cartoon characters.

I could go on. Maybe I will, another time. Suffice to say that if all you did when visiting Japan was travel about on the rail network, you’d have the time of your life. Actually, that ‘if all you did’ might equally apply to meeting Japanese people, using the bathroom or going to an onsen, but more of that later…

We only really knew Hiroshima from what we’d learnt at school about the war, and the constant re-watching of some of the post-bomb footage that was so much a part of growing up. So our association was with some harrowing images and real human tragedy. And so we were always going to start our visit by paying our respects at the Genbaku dome (the derelict shell of the only building that remained in central Hiroshima after the bomb) and the rest of the Peace memorial park. As you’d expect, the whole experience was sombre, respectful and challenging; it was definitely peaceful, but in an almost collegiate sense, hard not to be mindful of the people from all nationalities, but mainly Japanese, everyone with their own connection. ⌗3’s Japanese friend told us that almost every school in the country will organise a trip to Hiroshima once a year – there were loads of schoolkids of all ages, all in identical uniforms, being steered through the park and the museum in respectful silence – probably as impressive as the museum itself. The memorials in the park are really moving – one is to the students killed on August 6th; thousands had been ‘mobilised’ into the city to help with building demolition to build fire breaks against future bombings, so were all working outside – another is a memorial to the children who had been killed – many in their schools in the centre of the city. This statue is of Sadako Sasaki, two years old when the bomb dropped, and severely injured, and who died of leukaemia ten years later. She’d been inspired to fold paper cranes by the legend that if you fold a thousand cranes you’ll be granted a wish, so set out to do that, using medicine wrappers and paper given to her by other patients. So that’s why folded cranes became a symbol of peace; thousands of them are brought as gifts to the memorial each year.

Away from the peace park, we ambled around Hiroshima, still very conscious of its history, not least as every building has been put up in the last 75 years, but the feeling of peace and respect seems to have travelled alongside the rebuild – there’s more greenery than any other city that we visited; it’s got a peaceful feel about it which is really calming. Having said which, our quest for Hiroshima okonomiyaki took us to Okonomi Mura, where there are five floors of absolute chaos, where you queue to sit on a low stool and see a chef sweating over the griddle between the two of you. Probably the most disorderly way of getting a meal possible, least of all for three hungry people, so we opted out.

Next day, we took the ferry to Miyajima island for a trek up to Mt Misen. The ferry passes a ‘floating’ Torii gate in the bay, then you troop off onto the island, which is sacred, to the extent that apparently no-one has ever been born or died there. Hard to believe, as there were lots of people on the ferry, including kids going to school in both directions, and the hike to the top of Mt Misen is fairly arduous, although for the faint hearted there is a cable car (ropeway) to the top. We hiked up, which took a couple of hours, punctuated by shrine visits, amazing views, and treks through bamboo forest. Got to the top, wandered around for a bit, inspecting the eternal flame that had already burnt down a couple of shrines, then got the ropeway down to the port. Deer everywhere, especially around the port, where they’re quite keen on getting involved with your lunch.

Back to Hiroshima on the ferry for more wandering about, ending up at a Chinese vegan place where we ate mabo nasu and drank lemon sours made out of huge industrial Suntory optics. Wandered back to our hotel through what turned out to be the red light district – 8 story buildings with a bar on each floor. Had a couple of Suntory highballs in a meat restaurant, next to some sararīman (salarymen) who were cooking their meat on a central burner; plastic over their hanging jackets so they wouldn’t stink afterwards. We had a look at the menu out of interest, which included uterus sashimi & beef lung, which had a direct translation of ‘the fluffy texture makes it popular with women’. On the way out we were offered a selection of mints and chewing gum, which were probably quite helpful if your breath was stinking of uterus and lung.

Morning run the next day to Hijyama park, we were out at 0730 and mixing it on the roads with loads of kids in their neat uniforms pedalling to school. ⌗3 teaches kids as young as 4 through to high school and told us quite a bit about the school regimes that they have – pre school activities like swimming and athletics, school, then maybe a language class or two and more activities before they return home, sometimes as late as 10-11pm. Quite young kids take the train to school on their own, and each station on most train lines has its own tune that plays when the train stops so they know when to get off. ⌗3 sometimes has to wake up kids who are asleep on his train home from work if they’re asleep, and also has to deal with kids falling asleep in his classes if they’re at the end of a long day.

Toured around the faithfully rebuilt Hiroshima castle, then finally got our Hiroshima okonomiyaki – brilliant food – layered batter; cabbage; shrimp; soba noodles; seaweed; spring onions, (kewpie) mayonnaise; okonomi sauce (secret ingredient: worcester sauce); pickled ginger. All cooked in layers on a griddle in front of you, and quite a huge meal. When we got back from Hiroshima, ⌗3’s friend N told us that it was quite unusual for people to order a okonomiyaki for each person, information that would have been quite useful had we known it in advance of ordering. Theres a phrase in Japanese (hara hachi bun me) that translates as 80% full- eating to this level is considered a very good thing in keeping body and mind in good nick. You can read about this (and lots of other interesting stuff) in Adharanand Finn’s excellent ‘The Way Of The Runner’, all about the world of Japanese running. To the best of my knowledge, there’s no phrase for 120% full, which is very much how we felt after exiting the restaurant.

Took a train to Onomichi and found our hotel in the dark. We went there to cycle part of the Shiminami Kaedo route, which connects some of the islands south of Hiroshima. We rented bikes that were at least two sizes too small for me & ⌗3, then took an early morning ferry across to Mukaishima island with hundreds of school kids, then cycled across some spectacular bridges and across Mukaishima, Innoshima and Setoda, where we dropped the bikes off and caught another ferry back. It wasn’t a massive ride, but twenty miles on clown bikes felt like enough, and we needed to get back so we could get our Shinkansen back into Kyoto. But we managed to spend a bit of time in Setoda, – apparently the lemon capital of the region, and one of those places where everything follows that theme – if you’re ever in Japan and you feel the need to buy a lemon, a lemon fridge magnet, a lemon themed cycling shirt or a lemon cake, the do head for Setoda.

Stopover in Kyoto to pick up some clean clothes, then the Shinkansen to Tokyo – again, marvelling at 60-year old technology that whizzed us along at pace with loads of clean legroom. We’d got seats on the Mt Fuji side of the train, so it was a bit disappointing that it was so cloudy, but we would have passed it so quickly we might not have had much of a chance to see it anyway.

And so to Tokyo, the world’s largest city, home to 37 million people, most of whom had been good enough to turn up to the station to welcome us. We saw quite a bit of the rest of the population over the next few days as well, dodging them on early morning runs to the river, avoiding their purposeful striding around the designer shops at Ginza Six, and definitely keeping out of their way at the Shibuya scramble crossing, where up to 3,000 people cross whenever the pedestrian man turns green. We had a fantastic hotel room with a view of the Tokyo Skytree tower, and, although we were on the 20th floor, we couldn’t see to the edge of the city. Or anything green, at all. If we looked hard, we could see the elevated highways and the Shinkansen lines, so it looked a bit like a scene from Metropolis.

Mrs E had told me that the fashionable part of Tokyo to see and be seen in was Harajuku, which we went to on our second day, and where I was reprimanded by Mrs E for not remembering its name or how to pronounce it. On further investigation, however, it became clear that the reason she felt the need to go there was partly driven by the lyrics to ‘I’m A Cuckoo’ by her second favourite Scottish indie band, Belle And Sebastian. I’ll do a blog some time about her first favourite – Hamish Hawk, where she is apparently, Gold AAA Pass Fan ⌗262, but that will have to wait. In the meantime, she bows to few others in her encyclopaedic knowledge of the twee Glaswegian jangle-merchants, and in particular, their singer and lyricist Stuart Murdoch. In ‘I’m a Cuckoo’, Murdoch rhymes, not so much with an elegant pen, as with a mallet:

I’d rather be in Tokyo

I’d rather listen to Thin Lizzy-oh

Watch the Sunday gang in Harajuku

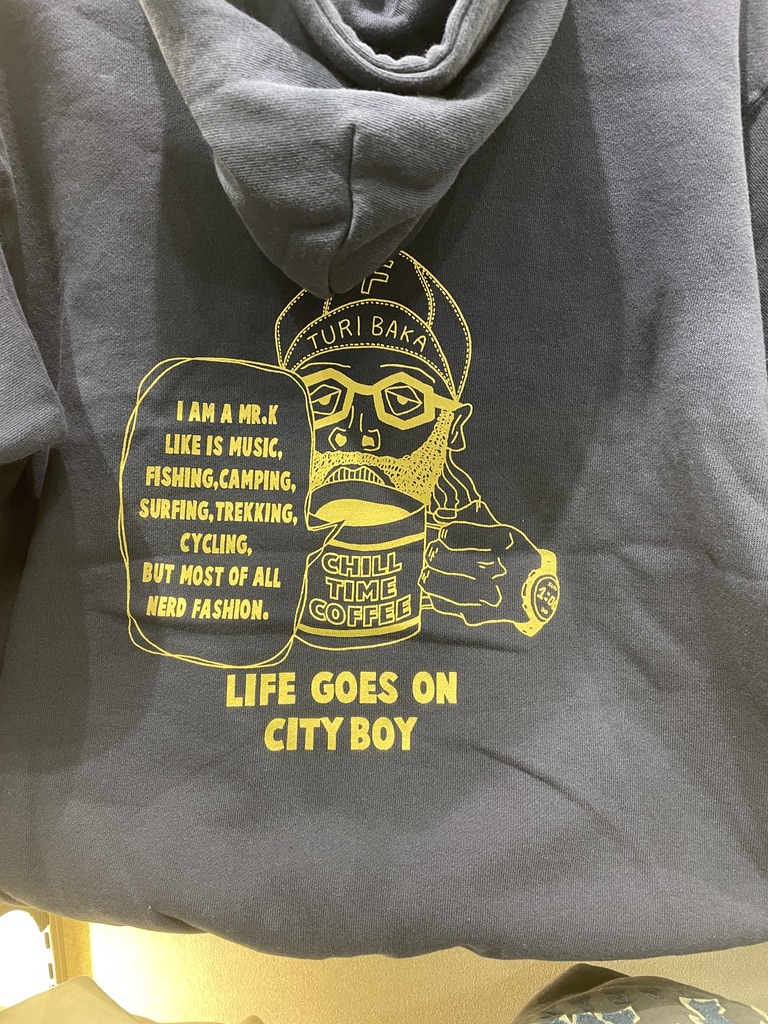

Mrs E thinks it’s a work of genius, but I guess it’s our differences that keep us together. But Harajuku was very good for the second hand shops that sell loads of vintage clothing. We were in the States a couple of years ago, and arrived with very little luggage, hoping to pick up vintage shirts and jackets in thrift stores, and were hugely disappointed by what we found. And it looks like the answer is that it’s all in Tokyo and Osaka, where there are a load of shops selling letter jackets, Arrow shirts, Levi’s, bowling shirts and leather jackets. You see a lot of people shopping for this stuff, but very few people wearing it – the style of all the cities we visited was much more French in its look – muted colours and simple styles. It would be fairly easy to dress just by shopping in Muji and Uniqlo (which is where the other crowds of shoppers were). There are exceptions, particularly for girls in their late teens and early twenties, who are quite keen on the American oversized t-shirts and sweatshirts, preferably with some writing on. If they’re from thrift stores, you might see a young girl wearing a shirt saying ‘Proud Republican Father of Five’ or ‘Little Falls Idaho – PTA camp out 2010’ or something similar. If they’re new clothes, it tends to be an assortment of random words, a bit like the sweatshirts that you saw in the UK in the 90’s which had words like Authentic, Original, Brand in a randomised order. I saw a really expensive sweatshirt in a designer shop that read: ‘I am a Mr K. Like is Music, Fishing, Camping, Trekking, Cycling but most of all nerd fashion. Life Goes On Cityboy. Chill Time Coffee.’ Maybe the designers are being taught English by ⌗3, I don’t know.

We did manage to find a bit of greenery, in the form of Ueno park, which we visited on Sunday, with lots of relaxed locals and tourists enjoying the trees, and the street entertainers, really good fun, even if they did have something of the childcatcher in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang about them. Hardly anyone visiting the museum of Western Art though, so we had a couple of hours of air conditioned comfort in touching distance of paintings by Miro, Picasso, Monet and Jackson Pollock that had been bought up over the years by Kōjirō Matsukata and then left to the country in 1959. We’d been told that a visit to the Hibiya Okuroji market under the railway arches was a must, but after a few hundred metres of wall to wall tat, we re-classified it as a must not, and went for something to eat. We hunted for over an hour for T’s Tan Tan vegan restaurant, which we eventually found next to one of the rail platforms in Tokyo rail station. Really worth the hunt, and indicative of the whole underground worlds that exist in all the major railway stations that we went to. There are supermarkets, fashion malls, specialist shops and amazing restaurants all hidden away, and very much part of the commuter culture. You don’t eat on Japanese trains, with the exception of the Shinkansen, so if you fancy some dumplings, ramen, sushi or really anything else, you eat at the station before or after your journey. The food is really fresh, fast, and because you’re eating at a restaurant, there’s no litter afterwards. Another thing about restaurants – the culture doesn’t allow for tipping, which is seen as a bit of an insult. What you do is go in, have a lovely meal with excellent service, get the bill, then pay the exact amount at the till as you leave, safe in the knowledge that everyone in the restaurant or bar is being paid a living wage. Doesn’t that sound good?

We were staying near the Senso-ji shrine, so trawled round there the next morning, a beautiful place and a great example of how all Japanese cities maintain these places side by side with new development. Senso-ji is really big, and full of tourists, but shrines exist on most streets, people stop, pray, leave an offering and move on as part of their normal day. Found another green part of the city in the imperial palace and grounds, filled with 2,000 Japanese black pine trees, and in the evening made our way to the Tokyo tower – a 333 metre tall structure which is lit up like a neon Christmas tree at night. In any other city, this sort of structure would be in a park, but in Tokyo, there are skyscrapers, office buildings, apartment buildings, churches and shrines all nestling up against the base.

A slight divergence at this point. It has always been the aim of the Emu to keep things very much above the waist, but every now and again, an exception needs to be made. And today’s exception comes in the form of the Toto toilet, Japan’s standard facility in a world of substandard facilities. You find these toilets, not just in hotels, but in homes, low end restaurants and public toilets. Let me just tell you about the basic controls. There’s nothing to control the heating for the seat, it just seems to know what’s comfortable. But reading right to left, you can press the automatic deodoriser, the wand clean (not sure what that does) , the ‘music’ button, which plays white noise to cover up any noises that you might make yourself, the front bidet and the rear bidet, both of which deliver a stream of water which you can, of course, adjust in pressure or temperature. Now, I’ve never liked spending more time than I need to in the toilet, but I think if I was the proud owner of the latest Toto model and, say, a portable radio, I might enjoy most of my leisure time there. Finally, there is a level of (ahem) cleanliness that the Toto user experiences that I think will be unknown to the non-user. We decided some years ago, for the sake of our marriage, that I would never waste money on white underwear, but if we lived in Japan, those white Muji boxers could become a real possibility.

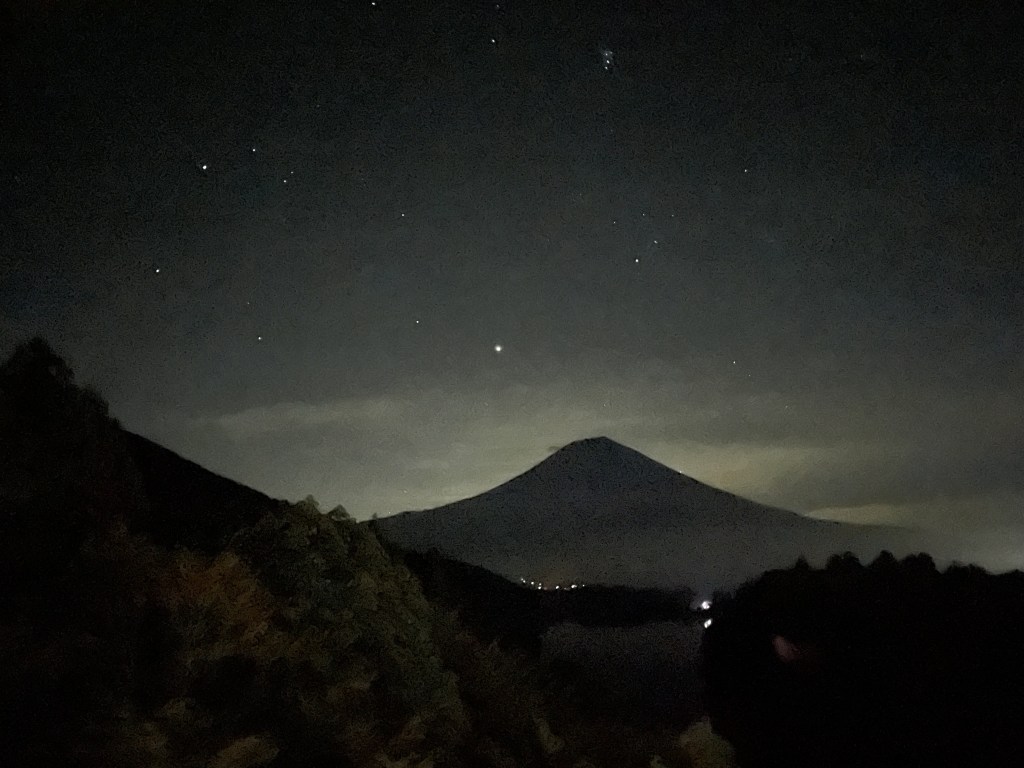

We took the Shinkansen to Shin-Fuji then two bus rides into the country outside Mount Fuji – this was a bit of a challenge as our non-existent knowledge of Japanese meant that we couldn’t match bus stops to bus, but we almost managed it. Almost, because we got off at a campsite rather than the hotel, which was fortunately only a 15 minute walk away. This would have been fine if we’d not bought most of Muji’s autumn collection in Tokyo the afternoon before, so we turned up at the hotel carrying multiple bags, sweating buckets and still no further on with our language skills, beyond hello and thankyou. After a fairly stilted conversation between us, the receptionist and Google Translate. we got pointed in the general direction of the room, which we’d been told didn’t have a bathroom, as the hotel had its own onsen. The room was fantastic, with a window that, without cloud, would have been completely filled with the perfect triangle of Mt Fuji, and no furniture – we’d been told that we needed to make up the futon bed from the cupboard when we wanted to sleep. We decided to give the onsen a go – if you’ve not heard of an onsen, it’s a combination of a bathhouse and a mineral bath. It’s strictly separated men and women, you need to be completely naked to take part in the bathing, and there are a number of fairly complex rules that you need to follow. You get undressed in a changing area, then holding a miniaturised modesty towel, pass through a curtain into the onsen itself. There you sit down on a plastic seat and wash yourself very very diligently – you mustn’t let any dirt or soap go into the mineral bath. Then you lower yourself into the onsen bath, making sure the water goes no higher than your shoulders, and that your modesty towel doesn’t touch the water. And finally, you’re doing all this in respectful silence and, in my case, avoiding eye contact at all times. It’s more fun than it sounds, honestly, and you do feel remarkably clean afterwards.

We went to bed that night on the futon mattresses, both on our sides and looking out of the window, and after an hour or so, the clouds lifted and the mountain was lit from behind by the moon, filling our room with a huge dark outline. The dilemma of whether to sleep or not while we were seeing this wasn’t helped by the need to follow the results of the Norwich vs Leeds game, which had kicked off at a very unreasonable 3:45 am. Dipped in and out of a sleep, during which I dreamt of seeing a huge mountain, Norwich going ahead and Leeds equalising, then woke up at dawn as Mrs E was photographing the sun touching the mountain for the first time, unable to distinguish dreams from real life.

Negotiated two more buses back to Shin-Fuji, again getting off at the wrong stop, although this time on the instruction of some Indonesian tourists who’d been at the hotel, so at least it was someone else’s fault for a change. Onto the lovely Shinkansen again and back to Kyoto to do our laundry and sort out some food, then off again in the morning for ⌗3’s two days off. Firstly to Nara, a beautiful town completely overrun by sacred deer, who all had limited road sense and enthusiastic appetites. Up to the astonishing Todaiji Temple (the largest wooden building in the world, fact fans) with its 18m high Buddha, built over three years in 762. Absolutely stunning, and really hard to do it justice with words or photographs, although this site does a pretty good job.

Hiked through the Fushimi Inari gates – it was teeing it down with rain so very slow progress climbing up, so ⌗3 took us on a side hike, away from the gates and up past hundreds of shrines and jungle forest to the top, by which time there were very few people about; we descended down precarious slippery slopes in the dark with all the gates, if not the steps, lit up to guide us. There are around ten thousand torii gates, all painted in the familiar vermillion colour, each sponsored by a business keen to associate themselves with the passage from this world to the next. .

Then back to Kyoto for vegetarian ramen with ⌗3’s Japanese friend, who we lightly grilled on just a few of the very many things that we wanted to understand about Japan. Like everyone we’d met, she was so thoughtful and considered in her explanations. Although the stricter Buddhist practises may be less obvious in current Japanese culture, there’s definitely a sense of internal comfort and a very clear reluctance to make an exhibition of themselves that still permeates. It all makes for a calm amongst the chaos; you see this all the time when you’re walking about in cities – people queue politely for everything, including crossing the road – no pedestrians ever step onto the road unless there’s a green man, even if there’s no traffic about.

To the railway museum in Kyoto the next day – fantastic stuff, made all the more enjoyable by the adorable kindergarten school parties in matching uniforms and hats, holding hands in pairs in a crocodile formation, and doing the little head bow thing when they met someone, and even when they came across a particularly impressive train. Then to Osaka, where we got to the 39th floor of the Umeda sky tower, before Mrs E discovered new levels of vertigo from the glass walled lift and we had to abort the trip, then South to Dotonbori, which is like a constant stream of Times Square billboards; really lively and quite a contrast with Kyoto. Osaka is huge, second to Tokyo but still the world’s 10th largest city, with 19 million people. And the Dotonbori area feels like a desperate last party, with hundreds of bars and clubs and restaurants vieing for attention. We met with ⌗3’s American friend here and had a great night drinking beer then eating pizza in a rooftop restaurant before just catching the last train back to Kyoto.

Next few days were in Kyoto, still loads to explore, both at night and during the day. We had an unintended big night out with ⌗3 and a couple of his friends, which started with a couple of cans by the river. This is the place where young people go to hang out, and where they just go on a date, a couple of cold drinks from the konbini, sitting together looking out over the river. It’s all quite sweet, respectful and well behaved – I went for a couple of early morning runs along these stretches of river and there was never a scrap of litter from the night before. Our evening got a little messy as we progressed from bar to basement restaurant to hidden bar, where we drank glasses of sake and shochu and then to the Ing rock bar, hidden away in an apartment building, where they serve serious strength Sapporo beer until 5am every morning, and play very good music, very loudly. ⌗3 told us that he’d been here before, but stood no chance of finding it without his friend J, who was with us and described it as his second home. Grateful as ever for Mrs E’s relative sobriety – she’d stopped drinking several rounds before I did and successfully steered us both home. I think I was suitably contrite and apologetic the next day, which was a bit of a hungover write off.

To the Ginkaku-ji temple – a huge Japanese garden surrounding a temple complex in the centre of the city. Serene surroundings, really green, with moss and rock gardens intersected by waterfalls, rivers and statues. Very few people about, which made it even more peaceful.

⌗3 had a late start the next day, so we took the train out to Arashiyama, where tourists go to see the temples and shrines; we hiked through the bamboo forest, then up past the Jojakko-ji Temple to look back over Kyoto, then across to the other side of the river to Kameyama-koen Park, where at the top you find yourself in the middle of a monkey sanctuary. We were warned in the strongest terms on signs going up to avoid eye contact with the monkeys, and not to point cameras at them, which seemed to be advice dutifully ignored by most of the other tourists.

And before we knew it, it was time to head home. A last trip out to Kusatsu, where ⌗3 works, a fair sized city which seems to centre around a huge shopping mall, which includes not only the English school, but a sushi restaurant that delivers the food to your table on miniature Shinkansen trains. Clearly this was not an opportunity to be missed, particularly for Mrs E, so that’s where we had our last meal together.

Did a bit of wandering around before ⌗3 had to go to work, then said our goodbyes. I never know what to say when I say goodbye to any of my kids, I think it’s because I might say the wrong thing, and one day, that’s all one of us will be left with. So I tell him that I love him, and so does Mrs E, and he says it back, and then we don’t see him anymore. and Mrs E has a bit of a cry, so we try to distract ourselves by wandering around Muji one last time. Then it’s time for some serious travel back, which neither of us really wanted to do, but there’s always stuff to get back to, even if it has to be reached with packed planes, dirty trains and dodgy taxis. And the dog was very pleased to see us.

We managed to get through the best part of three weeks on two words which I’d recommend learning. We did try to learn a lot more but very little stuck. So if you’ve managed to get this far, I’m very grateful…Arigato gozaimasu ! x