If me & Mrs E had a thing called a bucket list, then it’d be quite a long one. Incidentally, why is it called a bucket list? Well, fact fans, it’s because a screenwriter wrote a film based on his own list, which he’d originally titled ‘Things to do before I kick the bucket’, which then got abbreviated to ‘The Bucket List’. What you learn on the net, eh? But the reason our bucket list would be quite long is that there are so many things that we’ve not done that we’d like to do, so many places we’d like to see, so many hills we want to climb, so many bodies of water that we want to swim in, that it would be exhausting just making the list. And then we’d have to look at the list, and try to ‘achieve’ it, so we’d always feel like we were competing with ourselves. So, two things – we don’t have a list, and we don’t tend to go back to places, unless there’s really good reason. And our reason for going back to Japan (see here for the first time around) was very much in the shape of #3, and we both miss him more than words can say. Having said which, I’ll give those words a go, very possibly in the next couple of paragraphs.

Actually, saying ‘we’re back in Japan’ isn’t strictly true. We’ve just had a fantastic visit, and we’re currently two hours into a 14 hour flight to Amsterdam, which should allow a bit of time for reflection. We’re currently a couple of hundred miles to the east of Russia, heading towards Alaska and Greenland. Mrs E is watching a film to my left, and the Spanish guy to my right has just started snoring after a reading a chapter of Jordan Peterson’s latest book. So he’ll be good for a cheery conversation about populism and the death of late stage western capitalism a bit later on. If only I knew the Spanish for ‘my pronouns are…’

And I’m listening to Abbey Road on some brilliant noise cancelling headphones that I bought for the equivalent of £30 in a Japanese shop where I was bowed to around a dozen times by four different shop workers. And I’m listening to that particular album because I downloaded it after our last conversation with #3, in a basement music bar where they not only allowed smoking, but actively encouraged it, where most of the drinkers there seemed to know #3 by name, and where there was a full PA and drum kit set up just waiting to be used, and where, according to #3, ‘they’re always playing the Beatles whenever I come in’. And as we made our way down the stairs, there were the first few chords of ‘Come Together’, and it felt like Abbey Road had been cued up for our arrival.

And because none of us can ever say how much we’re going to miss each other, and how much we mean to each other, even though it’s our last night together, we end up having a conversation about the Beatles. And it’s not one of those awful blokey factual conversations about how George Martin positioned the microphones just so, to pick up the guitar feedback; or Mal Evans’s contributions to ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’; or the meaning of the numberplate on the front cover; no, this one is about the music, and the point at which the segues work, and the way that the album showcases four different talents in a way that none of the other Beatles albums really do. It’s a lovely conversation that lasts as long as the one beer that we’d promised each other, and I find myself looking at him, not for the first time, just in awe of how perceptive and funny he is, and how that funniness masks a deeper thinking that must be really hard to articulate in a different culture. And then, just as ‘Her Majesty’ fades out and the barman puts on a Weezer album,, which couldn’t be a better cue to leave.

And then it’s time to say goodbye, thankfully only until Christmas, and as we’re saying slightly rushed goodbyes at the subway station, an ambulance speeds past, and Mrs E has a bit of a wobble, about what would happen if he was ever taken ill. And somewhere in all of that is the reason for missing him; we’ve actually spent more time with him over a concentrated period that with any of his brothers in the last couple of years; they’re all living their own lives and there’s a few hundred miles between us all in the UK. But with this one there’s the fear of how he’s able to manage his own happiness in a world where he can’t really share his emotional thinking. Does that make sense? I guess what I’m saying is that there were little bits that evening where the three of us just tuned into the same wonderfulness of shared music, like on ‘Carry That Weight’ when it cuts into ‘The End’, or the bit where the gap between ‘Polythene Pam’ links to ‘Bathroom Window’ by Lennon shouting ‘Oh Look Out!’, where we can all agree that it’s genius, but it’s hard to encapsulate why, and it’s hard to imagine how he’ll tune into that with other people – even if his Japanese was perfect, that lack of a shared cultural reference might lead to a dissatisfaction. And then he might not be able to live his best life, whatever that is. And that, in a very roundabout way, is at the heart of why we’ll miss him.

But let’s get back to Japan – there’s some stuff we saw and did that was amazing, and some observations that might be old hat…but who cares – you can always skip past them if you’re bored.

What we did…

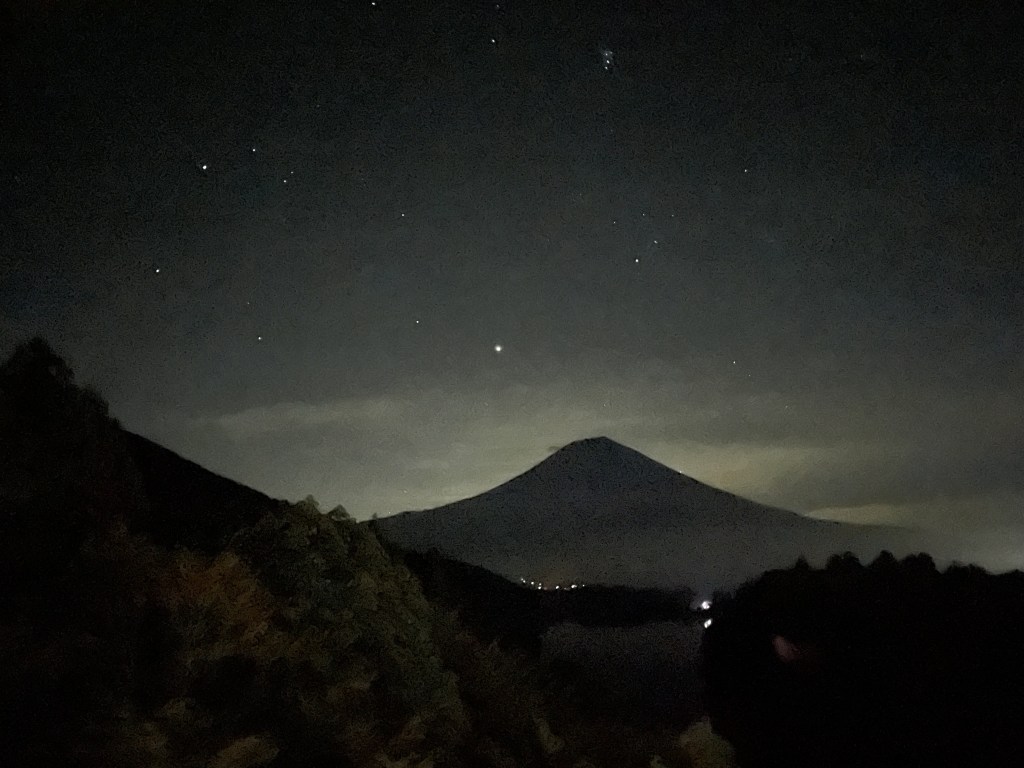

Get to Osaka, and like the old hands that we are, jump on the Haruka ‘Hello Kitty’ themed train to Kyoto – spotlessly clean and on time, of course, head across to Kyoto to meet #3, and he looks so tall and healthy, he’s been looking after himself and he can’t stop grinning and neither can we, and it’s all rather wonderful. We stay in a hotel next to his flat so we can store our bags at his while the three of us fly to Sapporo, which is about as far North as you can go without ending up in Russia, and where we get to meet #2, who is 3 weeks into a month-long trip in Japan, so we get to hang out with the four of us, hiking, sightseeing, running, and just being in each other’s company for a few days. A day trip to Otaru, which is a bit like a mini Disneyland in the middle of an industrial town. We wandered off the beaten track a couple of times and found ourselves in about the least Disneyland place you could imagine. But #3 found an Anpanman character for his rucksack, so well worth the expedition.

There seems to be a fascination in Japan for old music boxes; especially the ones that play big metal disks against a strung mechanism. There are a couple of museums/shops in Otaru that have lots of these on display, often with very creepy Pierrot figures rotating to plinky sounds – Mrs E declared the shop we went to as possibly the creepiest place she’d ever been to:

A strange last night in Sapporo, where we find ourselves at a fabulous frantic restaurant being run by one elderly woman who was doing everything, then spilled out to find ourselves outside the Atomic Cock Tattoo Parlour, which, fortunately was closed, and then escorted by a complete stranger, who’d taken a shine to #3 (and to me, once #3 had lied to her that his dad was a personal friend of Harry Styles) to the beautifully named ‘Bar Foul’, where we were the only punters, and the only non-Japanese sign asked patrons not to throw up in the bathroom.

Back to Kyoto, and a goodbye to #2, so he can start his new job, which is going to be a bit of a contrast to how he’s spent the last four weeks, hiking in rural Japan with only a couple of words of Japanese and his winning smile to get him through.

A few days in Kyoto where all of my Duolingo Japanese deserts me, and the only thing I can remember is (Watashi wa nihonjin desu) (I am Japanese) which got a few polite laughs but didn’t really help beyond that.

A visit to a football match, Kyoto Sanga at home to Kawasaki. Now, I go to Carrow Road to see Norwich play every home game – a penance that no-one really deserves, but there’s a comfort in football that I might have tried to describe on these pages before. Carrow Road holds just over 27,000 people, and on a good day, will be a noisy, shouty, exciting and chaotic place to be. Kyoto’s home ground holds 5,000 less fans, and has an atmosphere that you’d expect from a stadium twice its size. Twice the noise of Carrow Road, and probably ten times the effort put into making this an exciting place. Every seat sold out, home fans pretending to be ultras at one end, and at the other end, fully a third of the total seats filled by travelling Kawasaki fans. (Note at this point that these two cities are about 5 hours apart by car – that would be like Norwich Fans taking about 10,000 to Middlesbrough on a Friday night, which has never, and will never happen). The game itself was not overly exciting, but the fans at each end didn’t stop jumping and singing (all in perfect unison) for the whole game. At the end of which, all the players went around the pitch applauding the fans, before lining themselves up in front of the directors’ box, and bowing in unison. And afterwards, everyone filed out without pushing fans from each side shoulder to shoulder, and all carrying their own litter, which everyone queued up to give to the stewards holding bin bags on the way out. Norwich are at home to Bristol City on Saturday, and, although I’m looking forward to getting back to that dirty, grubby untidy match day experience, I can’t help feeling that I’ve recently experienced how it could be done – maybe any British football club exec who claims that it’s all about the fans should whisk themselves off to the Japanese leagues for a view on how fans actually like to be treated.

A couple of day trips to Kobe (wonderful, calm, non-touristy) and Osaka (manic, and crashing a party for one of #3 friends, at least one too many drinks for us all), then, having spent a fair chunk of change on the Shinkansen, south to Nagasaki, where we found ourselves in the middle of a three day festival of dragons and quarter size ships being paraded by enthusiastic monks through the busy streets. Tried not to look too hard at the food stalls, which seemed to specialise in sea creatures on skewers. We later learnt that we’d missed the real festival food favourite, which involved cramming as many quails eggs as possible into the inside of an octopus. Wandered around the Peace Park and the Peace Museum, which was quite sobering, and hiked up to the top of Mount Anasa to see the views over the city; we could see where the bomb had dropped and the destruction it must have caused – although Nagasaki was the secondary target for the second bomb (the drop on Kokura had been abandoned due to cloud cover and smoke) – it was effective in the same way as Hiroshima had been – both cities are surrounded by mountains, so the radiation was contained.

Nagasaki was really important as a manufacturing city as well, and that had partly come about through the semi-colonialisation of the city in the late 1800s, by shipping and manufacturing entrepreneurs like Thomas Glover. It’s worth wandering around the Glover estate if you get the chance – it overlooks the city from the other side to Mount Anasa, and is presented with quite a bit of affection and respect for the families that came over and made a bundle from Japanese trading. And when you’ve done looking at colonial style homes built by Japanese carpenters, and tropical gardens on the Glover estate, then you can head to the waterfront and visit Dejima, an artificial island which has now been absorbed into the port area, that was set up as a trading post, initially for the Portuguese , until the mid 1600s, and then the Dutch, who ran it until 1858. Again, colonialism presented with some affection, which felt a bit odd, as those words don’t normally go together but there’s (I think) a genuinely positive feeling about how Nagasaki managed to assert itself through western links as Japan developed into the twentieth century.

Back to Takeo-Onsen on the Shinkansen – we’d decided to stop for the night, based on the promise of a wood panelled hotel, and after a certain amount of searching, found it, just outside what the roadsigns called the ‘Hotel Town’. Wood panelled it was, and featured a number of items that would have fitted well into Mrs E’s ‘creepiest place’

It was, by any definition, a strange hotel. And made even stranger the next morning when I popped down to reception to get a coffee, to be accosted by a Japanese lady, well into her 90’s by any stretch, offering to DJ on one of the decks for me. Again, my Japanese failed me, and I must have given the impression that I thought that it was a good idea, and a full music box orchestration of ‘Rule Britannia’ was soon filling the ground floor at no small volume. If I could have ‘made my excuses and left’, as the Sunday papers used to say, I would have done. Instead, I just left. But even now, I can still hear that tune…

Back to Kyoto then, a couple of days decompressing from the Japanese Mrs Overall and her peculiar brand of morning entertainment, and then a last night with #3, which brings us back to the start of the blog.

So, if that’s what we did, what about the pithy observations?

- Americana is still writ large, but it feels like it might be fading…

Every city has a collection of secondhand/vintage shops where you can mix and match your eclectic wardrobe from a selection of tatty American castoffs. There’s an awful lot of western tourists in these shops, which makes a bit of sense when you look round and see Japanese people wearing much plainer or neater fashions. There are a few gothy and punky types wandering about, but American fashion is far from mainstream. As with most things, there’s a value in authenticity, and you don’t get the bargains that you might have found in the past – I saw a pair of brand new shrink to fit 501’s in a glass case in a shop in Nagasaki, prices at a cool ¥149,900 (about £750). Not my size, unfortunately. And for all the falling out of love with Americana, there was queuing round the block for Onitsuka Tiger trainers, which were more expensive than in the UK…

- The way of the Onsen

We returned to onsen life like we’d never been away, public baths in Kyoto, hotel onsens in Nagasaki and in Takeo-Onsen. Towards the end of the holiday, we were averaging a couple of onsens a day, alternating between hot and cold baths, saunas and sit down showers. We reached a state of cleanliness that I suspect we’ll never get again. If you’d rubbed your thumb against our arms or legs, it would have made a squeaking sound. Once you get used to the idea that this is Japan, so you have to avoid eye contact and still not look in the wrong place in a room of naked people, you’re fine. And don’t have a tattoo. And if you have to carry a modesty towel, don’t let it touch the water. And use a mat to sit on in the sauna. And wash yourself with cold water from a bowl before going in the cold pool. And wash down the sit down shower area before and after use. And don’t speak unless you’re spoken to. Honestly, it’s fine.

- Litter

There’s still no litter. I thought this was amazing first time round, and got to observe it a bit more this time. It’s not that litter doesn’t get produced – if you eat food from the combini convenience stores, for example, there’s loads of packaging – but there are very few bins and in the parks on the cities, so if you end up with some rubbish, you just put it in your bag and take it home to recycle.

- Trains

The four of us were travelling on the subway on #2’s last night, one of us made a joke that made all of us laugh, and an elderly Japanese lady shook her finger at us, and pointed to the sign that said no talking. Really embarrassing stuff, so much bowing and quiet apologising, but the point was well made. You don’t travel in Japan to make a noise and potentially annoy other people. You just get on with the journey in your own world. Apart from the Shinkansen, there’s no eating or drinking on the trains. And of course, no litter. Once you’re on the big trains, it’s like getting into a business class plane seat, and of course, they’re really comfortable, and spotless. We got a connection between Shinkansens on the way back from Nagasaki to Kyoto, so got to see the train being prepared. One cleaner per carriage, every tray table taken down, cleaned and dried then put back, then vacuumed everywhere – each carriage got the same treatment and it probably took about twenty minutes, just for the one hour shuttle to Hakata. And let’s face it, you’re not going to litter something that’s been looked after that well anyway, are you?

- About the language.

I made a commitment to learn a bit of Japanese so that I could at least try to say something other than thank you. I’m rubbish with languages so at least I didn’t disappoint myself – I am nearing the vocabulary of a toddler but have no idea how sentences fit together and my comprehension is still non existent. But there’s something straightforward about sounds with meaning that make up a language, even if they don’t always obviously fit to any of the three indecipherable alphabets. Kyoto (Kee yo to), for example, means big city, as it was the original capital of Japan. Tokyo (to kee yo), means city that’s big; it took over from Kyoto as capital in 1868. So there’s a logic there – getting to grips with it so far has been impossible, but I can’t help feeling it’s worth persevering.

- Toilets

It was a truly sad moment when, a few minutes before boarding our plane home, that I had my last sit down on a Toto Washlet. This was just for old times sake really, I didn’t need to use it, but I just wanted that nice warm feeling on the tops of my legs, and to hear the wand come out to give me a little colonic irrigation with some delightfully warm water. Honestly, if I lived in a house that had a Toto installed, I can’t see that I’d get anything else done.

That wasn’t the paragraph I wanted to end on, so here is a bit of final thinking – we will definitely head back to Japan, not just because #3 has extended his contract for a further year, but because we’re developing a real taste for even a light improvement on our understanding. And as you get a bit more knowledge, you begin to realise what you don’t know – I know next to nothing, for example, about history, politics, nationalism, language or literature from Japan. No ambitions at all to become an expert, but I know that getting to have just a little more understanding might be a lot of fun. So…back to the duolingo then. Shitsurei shimasu (possibly) x